Today I'm taking a page out of thrifty Brillig's book and re-posting something I wrote back when I only had a tiny handful of readers. For those of you who have read this before, you have my apologies; I wanted to participate in Music Monday this week, and I didn't have a minute to write something new. The following is from February 2007.

Last Friday night I was driving home from Book Group. It was late and it had been snowing for several hours. I love being alone in a black night with snow; it always reminds me of one of my favorite paragraphs in the world, the last sentences of James Joyce’s The Dead:

Karen, Melissa, and I had carpooled to Book Group over at Camilla's house in Golden’s Bridge, chatting the entire time. On the way home, after I dropped off my two friends, I turned on the radio. I had for company someone playing the piano. I half-recognized the piece, but there was something so different about what I was hearing that I didn’t make the connection for a minute or two. Then it hit me with a flash: it was Bach’s Goldberg Variations. And played on the piano, not the harpsichord—but it didn’t sound like Glenn Gould.A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It

had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark,

falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on

his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over

Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless

hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly

falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every

part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay

thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the

little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow

falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of

their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

I find it particularly appropriate to listen to this piece of music when the rest of the world is asleep. Bach wrote the Goldberg Variations for a Count who struggled with insomnia; the Count had asked Bach to write some clavier exercises to be played in the middle of the night, something to soothe and cheer him through long, sleepless hours. The Variations are named after the Count’s talented young harpsichordist, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg; I imagine the poor young man being roused from slumber on any given night to play for his patron, because the Count apparently never tired of hearing them.

The Variations were published in Bach’s lifetime, but for many years afterward were regarded as dry, rather difficult pieces to be played on the harpsichord. In the middle of the 20th century, however, a brilliant young pianist changed popular opinion of Bach’s piece forever.

I know Gould’s landmark 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations as well as I know any piece of music. I’ve listened to it hundreds, maybe thousands of times. It has been a great friend to me, as the Variations were for the Count who commissioned them. But what I was hearing Friday night was so alien: haunting, personal, almost painful in its execution, where the version I know—lively, technically flawless—evokes a detached, peaceful mood.

Puzzled, I drove on and thought about our Book Group meeting earlier. We had had a intelligent and compassionate dicussion of a modern classic: Angle of Repose, by Wallace Stegner. Its main character, Susan Burling Ward, has chronic myopia when it comes to the life she has chosen; throughout her life, she compares her situation unfavorably to that of her best friend, Augusta. She doesn’t realize that she has within her grasp all the ingredients for a wonderful existence.

Her interpretation of herself, the reader easily sees, is faulty. She has, in fact, married the better man; her life of ‘exile,’ as she terms it, has defined and refined her work as an artist, not limited it. One woman in our group raised a question: How do you know when to be content? In other words, when you are in the middle of living one of life’s countless challenges, how do you stop looking over the fence at seemingly greener grass? It’s a good question, and an old one, one that has given philosophers pause for centuries.

After a lot of thought on the topic myself, I think the secret lies in our interpretation of what we’ve been given. Happiness is a choice; for some it’s a harder choice than for others, but it is there all the same. One need look no further than Victor Frankl for proof of this truth.

I myself have been given all the components for a perfect life: good health, every temporal comfort, lovely friends and children, meaningful work, and a dear man who loves me. But if I’m not careful, I can take the route Stegner’s heroine takes. I can focus exclusively on what I see as being wrong: my weight; brain chemistry that defaults to a baseline level of melancholia; the current state of our yard; the child who is misbehaving on any given day: the list could go on for quite a while, if I let it. But that interpretation of my life is a sure path to misery; I believe this is one of the points Stegner is making in his beautiful book.

Once home, I sat in my dark car in the driveway for few minutes so that I could discover the identity of my mystery musician. At the stroke of midnight, after the last few notes of the Aria died away, Bill McGlaughlin came on the air and informed me that it was, indeed, Glenn Gould playing the Variations—but that this was a performance recorded shortly before Gould’s death in 1982.

This was the same music played by the same artist I thought I knew so well. But the interpretation was so different that it changed the piece completely. Older, wiser, at the end of his life, Gould let his life inform his art and transform it; he put himself wholly into his work, and both were changed thereby.

Stop looking over the fence and start doing all you can to green up what you’ve got. Take plenty of time to rejoice in its verdure, and take plenty of time pay respects to the Source of all that is good and green. It is advice simpler to write than it is to live, but the secret to happiness is in the interpretation.

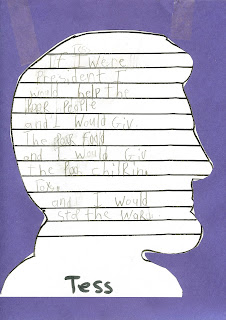

Here's the transcription, edited for spelling:

Here's the transcription, edited for spelling: